The Black Lives Matter movement has given a new impulse to decolonization in various aspects, focusing especially on public spaces, musea and school curriculum in the case of Belgium. At the University of the Philippines (UP) the new Decolonial Studies Programme at the Center of Integrative and Development Studies, with Frances Cruz as co-convenor, advocates for the decolonization of academia. However, the media plays an equally important role for the movement to reach the general public (Elliott 2016).

In this project, we focus on the representation of two ethnic minorities in the Philippines to identify colonial tropes in their characterization.

Chinese

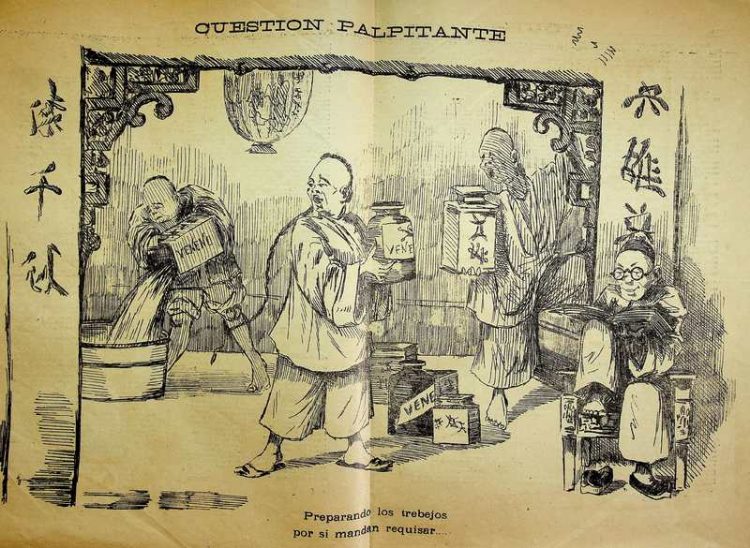

Contemporary relations of the Philippines and China have revolved around two main events since 2014: on the one hand, the Scarborough Shoal-Spratly islands conflict, and on the other hand, the foreign policy of the government of ex-president Rodrigo Duterte that signals a bipolar view of a world with the US and China as superpowers. Regarding the first event, Montiel, Salvador, See and de Leon claim that most of the news from the Philippine Daily Inquirer dealing with China in 2014 revolve around local fishing issues, International law, historical claims and nationalism (2014). These two last topics indeed hint to the recuperation of colonial discourses to build a new discourse on China. In addition, Teresita and Carmelea Ang See study the repercussions of the new wavers of Chinese immigrants in the Philippines and how both them and Filipinos often “find themselves embroiled in the popular discontent against China and Chinese immigrants” (See & See), reproducing old fears seen both in the Spanish and the US colonies (as seen in the collection of articles on this topic published in La Oceania Española in 1886 titled Los chinos en Filipinas, and in the US media and their focus on the Yellow peril).

The revival of this discourse is paradoxical, as it was also applied to justify systematic denegation of entrance of Filipinos in the US between 1898 and 1936 (Tyner 1999). It implies a number of practices already described by critics in other contexts. Anibal Quijano describes in Coloniality of Power how colonial structures and discourses persist in the Latin American republics and problematizes modernity as an Eurocentric concept (Quijano & Ennis 2000). Furthermore, Milica Bakić-Hayden applies the notion of nesting orientalism to ex-Yugoslavian republics as “a tendency of each region to view the cultures and religions to its South and East as more conservative and primitive” (1995). Taking into account the problematization of modernity proposed by Quijano, this can be related to an Eurocentric view which portrays as negative certain features of “conservatism and primitivism”. Finally, Lisa Lau highlights the current uses of orientalism and of Re-Orientalism as a practice carried out by diasporic oriental subjects as insiders and outsiders of their own culture (2009).

Muslims

As with the Chinese, Muslims in the Philippines were similarly the subject of orientalist colonial-era rhetoric and discourse. This was particularly evident in official reports, textbooks, and personal accounts which referred to Muslims during the early years of Spanish occupation as moros

or “moors”, a term which not only evoked Spain’s history of its own conflicts with Muslims (Majul, 1999, p.89-90), but stood out as a distinct identity marker from the connotations of the word indio. Angeles (2009) explores how colonial discourses during the Spanish and the American rule

represented Muslims in a negative light as they meant an obstacle to their christianizing (in the case of Spain) and civilizing (in the case of the US) missions (32, 37-44). Such antecedents thus beg the question of whether significant changes can be found in representations of Muslims after the declaration of Philippine independence in 1946. Revealingly, it was during the post- independence period that armed revolutionary movements such as the MNLF and MILF were formed, with the former emerging shortly after the Jabidah massacre of 1968, in which a several Muslim army recruits were killed by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. The twenty-year period following formal political decolonization can thus provide insights into media representations prior to the conciliatory rhetoric of President Marcos towards Muslims.

- How does the

representation of Muslims and Chinese in the Philippines vary in the

printed press of the colonial periods and the immediate postcolonial

period (end of 19th c., 1935-1942, 1946-1960) and which representational

strategies were reused from one period to another?

- Do these

representations persist in the contemporary press?

- Are there changes in

the representation depending upon the language in which the newspapers are

written?

- Are there differences

in the impact of these historical colonial representations upon

postcolonial representations depending on the language of the colonial newspapers

(ie. do newspapers in English have more influence in postcolonial

newspapers even if they were in Tagalog)?

- Exposing the coloniality of discourses on minorities in the Philippines in the contemporary media (Chinese and Muslims).

- Contributing to the reflection on the necessity of decolonizing discourses in media and academia.

- Using digital tools and training in their use to expose colonial discourses and critically reflect on their current validity.

The corpus that we have analyzed is the result of two initiatives:

(1) On the one hand, the digitization of colonial Philippine newspapers (1850-1900) carried out with a small project funded by BOF (Bijzonders Onderzoek Fonds) at the University of Antwerp in 2018. The newspapers were located in two Spanish libraries (Agustinian Seminar in Valladolid and Regional newspaper library in Madrid).

(2) On the other hand, the digitization of Filipino historical periodicals (1898-1970) withheld at the University of the Philippines performed with a VLIR-UOS TEAM Project called “Strengthening Digital Research at the University of the Philippines system: digitization of Philippine rare newspapers and magazines (1850-1945), and training in Digital Humanities” and led by Mike Kestemont, Rocío Ortuño and Dirk Van Hulle

Although back in 2018 the items digitized at UP were being uploaded to a public repository, a plain text version was not yet available and we had to fix it with Transkribus.

On the contrary, for the papers digitized in Spain in 2018, there was a plain text version that was not yet publicly online.

Due to the large corpus available and the presence of different time-frames and languages (we focused on texts written in English, Tagalog and Spanish), we used NLP methodologies to distant-read the corpus. The representation of Muslims and Chinese in the Philippines was then extracted by:

1. Training a model in Tagalog for transcription of newspapers in Transkribus (models in Spanish and English have already been trained).

2. Diachronic topic modeling: we extracted topics related to the ideas of Chinese and Muslim in the Filipino newspapers and visualized variation in topic prevalence across the given time period, namely around the period of decolonization and transitory periods between colonialisms.

3. Analyzing collocations: which words accompany the concepts of “Muslim”, “moor”, “moro”, “Chinese”, “Sangley”, “Tsinoy” and their correspondence/equivalence (ie. does “sucio” relate/apply to both, Muslim and Chinese?) which was studied with word embeddings.

Angeles, V.S. (2010). Moros in the media and beyond: representations of Philippine Muslims. Cont Islam 4, 29–53

Bakić-Hayden, M. (1995). Nesting Orientalisms: The Case of Former Yugoslavia. Slavic Review, 54(4), 917-931

Cruz, F. (2020). Publishing on the ‘international’ in the Philippines: a lexicometric inquiry. In F. Cruz & N. M. Adiong, International Studies in the Philippines: Mapping New Frontiers in Theory and Practice. Oxon: Routledge, 66-85;

Cruz, F. & Licayan, K. (2018). UP CIDS Policy Brief Series 18-007: Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (PCVE) recommendations. Quezon City: Islamic Studies Program, Center for Integrative and Development Studies, University of the Philippines, Diliman. Available at: bit.ly/cidspcve;

Lau, L. (2009). Re-Orientalism: The Perpetration and Development of Orientalism by Orientals. Modern Asian Studies, 43(2), 571-590

Los Chinos en Filipinas. 1886. Manila: La Oceanía española

Majul, C. A. (1999). Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press

Montiel, C. J., Salvador, A. M. O., See, D. C., & De Leon, M. M. (2014). Nationalism in Local Media During International Conflict: Text Mining Domestic News Reports of the China–Philippines Maritime Dispute. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 33(5), 445–464

Quijano, A., & Ennis, M. (2000). Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1(3), 533-580

See, T.A., & See, C.A. (2019). The Rise of China, New Immigrants and Changing Policies on Chinese Overseas: Impact on the Philippines. Southeast Asian Affairs 2019, 275-294

Seto, B. P. (2015). Paternalism and Peril: Shifting U.S. Racial Perceptions of the Japanese and Chinese Peoples from World War II to the Early Cold War. Asia-Pacific Perspectives. Spring-Summer 2015, 57-78

Tyner, J. (1999). The Geopolitics of Eugenics and the Exclusion of Philippine Immigrants from the United States. Geographical Review, 89(1), 54-73.